Generalizations are all good.

While I'm talking about that, let me just mention that the point of every software team is the same: build something great. A piece of software that fulfils its promises, is easy to use and learn, and adds real value to any human who wants to achieve whatever goals are incorporated in the system. That's great software. That's what we're all trying to do.

The Google search engine is an example of great software. I'm not a player, but I bet World of Warcraft is great software. The .NET framework is great software. There are beacons of design that inspire every software team, in every field.

When I first started managing software teams, I was a process nut. I just assumed that the best way to get great software was to join the process dots.

Back then, it was all about the planning. Plan the planning phase, and then plan out how you were going to build it, in painstaking detail, from the very beginning. Then you build it all (exactly as you planned it), test it all (exactly as you planned it), fix the bugs (but there wouldn't be many, because you had planned everything so well) and as long as everybody did everything precisely as you'd planned it, then perfect, delightful software would just fall into the customers joyous, enraptured hands.

At first I blamed the team for not following the plan.

Or me, for not enforcing the following of the plan.

Slowly, I began to realize that you could take the best, most clearly articulated plan, and still not ship on time, or ship anything good.

That planning wasn't enough.

This made me sad. A good plan should always win, right? It must be the people that are at fault. Everyone knows that people are the surest way to wreck any fine process.

So I turned to the dark art of winning hearts - of convincing people that the plan was good. Of finding out what it was that motivated people to do the best they can, with the devious plan of getting them to stick to my plan.

"This is a good plan. You should follow it. I will buy you a car if you follow it."

I couldn't afford to convince people. Then I realized that people only liked plans that they felt they had contributed to. That the team dynamics, and the people in the team affected the outcome even more than the plan.

And then I realized something that struck me at the time as really strange.

A loosely federated, appropriately sized team of talented people could produce great software without following the plan. That's what all this agile hooplah was about.

Because they loved it. They created it. They innovated. They made it better, once they'd made it once already. They would make late cycle changes that give risk managers heart attacks, and make the product twice as good. They felt like they owned the process that had let to its inception, and they were prepared to take responsibility for the project's success.

I'd already discovered the hard way, that a perfect process didn't guarantee the kind of amazing software I was looking for.

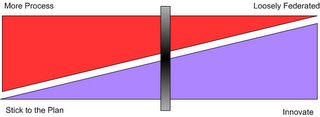

This morning, while trying to juggle the schedule, it dawned on me that this relationship is best illustrated with the following slider:

It's all about where you set the slider. Are you willing to enforce more process, in order to increase predictability? It will come at the expense of innovation. Want to increase innovation? Release the process constraints to increase flexibility.

Too far to the left and your biggest risk is boring software, that fails to inspire.

Too far to the right and your biggest risk is no software at all.

Attempting to move the slider in the middle of a development cycle is nearly impossible, and always extremely dangerous. At project inception, that's when you need to set the slider, and you need to do it with universal agreement from your team.

Generally speaking, of course...

While I'm talking about that, let me just mention that the point of every software team is the same: build something great. A piece of software that fulfils its promises, is easy to use and learn, and adds real value to any human who wants to achieve whatever goals are incorporated in the system. That's great software. That's what we're all trying to do.

The Google search engine is an example of great software. I'm not a player, but I bet World of Warcraft is great software. The .NET framework is great software. There are beacons of design that inspire every software team, in every field.

When I first started managing software teams, I was a process nut. I just assumed that the best way to get great software was to join the process dots.

Back then, it was all about the planning. Plan the planning phase, and then plan out how you were going to build it, in painstaking detail, from the very beginning. Then you build it all (exactly as you planned it), test it all (exactly as you planned it), fix the bugs (but there wouldn't be many, because you had planned everything so well) and as long as everybody did everything precisely as you'd planned it, then perfect, delightful software would just fall into the customers joyous, enraptured hands.

At first I blamed the team for not following the plan.

Or me, for not enforcing the following of the plan.

Slowly, I began to realize that you could take the best, most clearly articulated plan, and still not ship on time, or ship anything good.

That planning wasn't enough.

This made me sad. A good plan should always win, right? It must be the people that are at fault. Everyone knows that people are the surest way to wreck any fine process.

So I turned to the dark art of winning hearts - of convincing people that the plan was good. Of finding out what it was that motivated people to do the best they can, with the devious plan of getting them to stick to my plan.

"This is a good plan. You should follow it. I will buy you a car if you follow it."

I couldn't afford to convince people. Then I realized that people only liked plans that they felt they had contributed to. That the team dynamics, and the people in the team affected the outcome even more than the plan.

And then I realized something that struck me at the time as really strange.

A loosely federated, appropriately sized team of talented people could produce great software without following the plan. That's what all this agile hooplah was about.

Because they loved it. They created it. They innovated. They made it better, once they'd made it once already. They would make late cycle changes that give risk managers heart attacks, and make the product twice as good. They felt like they owned the process that had let to its inception, and they were prepared to take responsibility for the project's success.

I'd already discovered the hard way, that a perfect process didn't guarantee the kind of amazing software I was looking for.

This morning, while trying to juggle the schedule, it dawned on me that this relationship is best illustrated with the following slider:

It's all about where you set the slider. Are you willing to enforce more process, in order to increase predictability? It will come at the expense of innovation. Want to increase innovation? Release the process constraints to increase flexibility.

Too far to the left and your biggest risk is boring software, that fails to inspire.

Too far to the right and your biggest risk is no software at all.

Attempting to move the slider in the middle of a development cycle is nearly impossible, and always extremely dangerous. At project inception, that's when you need to set the slider, and you need to do it with universal agreement from your team.

Generally speaking, of course...

Comments

Post a Comment